In

the previous post We emphasized the value and importance of planning your

control system. In this post, we highlight some of powerful project control

techniques that you want to consider during your planning efforts and then

implement during the execution of your project.

Small work packages—This

was a point of emphasis during our discussion on building a WBS. If you recall,

there were two primary reasons for advocating small work packages: more

accurate estimates and better control. From a control perspective, if your work

packages are scheduled to complete within one (or at the most, two) reporting

periods, it is much easier to detect a delayed or troubled task. With earlier notice,

you are more likely to resolve the variance and protect the project’s critical

success factors.

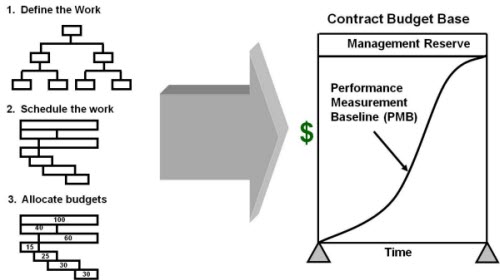

Baselines—A

fundamental control principle is to manage to baseline.

First,

establish a baseline. This is generally applied to the critical success factors

of schedule and budget, but you can apply it equally as well to

product-oriented aspects of the project, especially requirements. Second,

measure and report performance against the baseline. Third, maintain the

baseline unless there is a formal agreement to reset the baseline.

Status meetings—The

simplest, and most widely known, technique is the status meeting. Consistent

and regular status meetings help to keep everyone honest, accountable, and on

their toes—especially if work assignments are small and have clear completion

criteria. In addition, status meetings are powerful tools for improving project

communications and managing expectations.

Completion criteria—This

starts during project definition with defining the acceptance criteria for the

project, and it continues for each deliverable and work assignment. Answer this

question in advance for each deliverable and work assignment: “How will we know

when it is done?”. Understanding the completion criteria upfront increases

productivity and avoids many of the issues associated with status reporting on

work tasks, especially the infamous “I’m 90% done” syndrome.

Reviews—Reviews are

a key technique for ensuring quality and managing expectations on project

deliverables, and they can take many forms. The principle here is to plan for

the review-feedback-correction cycle on most, if not all, of your key

deliverables. Common examples of reviews are process reviews, design reviews,

audits, walkthroughs, and testing. In addition, reviews can be combined with predefined

milestones and checkpoints.

Milestones and checkpoints—A

key feature of most proven project methodologies is the use of predefined

milestones and checkpoints. These markers are important points to stop, report

progress, review key issues, confirm that everyone is still on board, and

verify that the project should proceed with its mission. Besides being a

powerful expectations management tool, these predefined points allow project

sponsors and senior management to evaluate their project investments along the

way, and, if warranted, redirect valuable resources from a troubled project to

more promising pursuits.

Track requirements—A

simple, yet often neglected, technique to help control both scope and

expectations is the use of a requirements

traceability matrix. The

traceability matrix provides a documented link between the original set of

approved requirements, any interim deliverable, and the final work product.

This technique helps maintain the visibility of each original requirement and

provides a natural barrier for introducing any “new” feature along the way (or

at least provides a natural trigger to your change control system). In

addition, the trace matrix can link the specific test scenarios that are needed

to verify that each requirement is met.

Formal signoffs—Formal

signoffs are a key aspect of change control management, especially for

client-vendor oriented projects. The formal record of review and acceptance of

a given deliverable helps to keep expectations aligned and minimize potential

disputes. Most importantly, the use of a formal signoff acts as an extra

incentive to make sure the appropriate stakeholders are actively engaged in the

work of the project.

Independent QA auditor—The

use of an independent quality assurance auditor is another specific example of

the “review” technique mentioned earlier, and it’s often a component of project

quality assurance plans. In addition, the quality audit can be focused on

product deliverables, work processes, or project management activities. The

power of this technique is in establishing the quality criteria in advance and

in making the project accountable to an outside entity.

V method—The V method is a term used for a common validation and verification

approach that ensures that there is validation and verification step for every

deliverable and interim deliverable created. The left side of “V” notes each

targeted deliverable and the right side of the “V” lists the verification

method to be used for each deliverable directly across. The diagram shown below

helps illustrate this method.

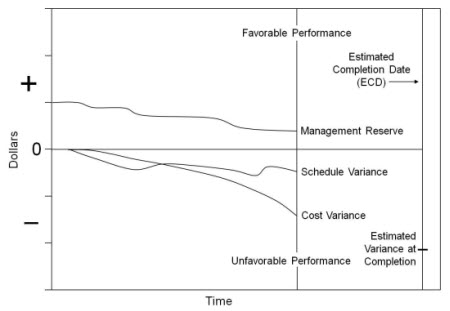

Escalation thresholds—Escalation

thresholds sound much more ominous than what they actually are. The purpose of

escalation thresholds is to determine in advance what issues and variances the

project team can handle and what issues or variances demand attention by senior

management. Often, these thresholds are defined as percent variances around the

critical success factors. For example, if the cost variance is greater than 10%

or schedule variance is greater than 15%, engage senior management immediately

for corrective action steps. The key value of this technique is that it helps

define tolerance levels, set expectations, and clarifies when senior management

should get involved in corrective action procedures.

Performance

Reporting

Another

key aspect of project control is measuring and reporting project performance. if

you keep these following principles in mind, you can adapt your performance

reporting process to best meet the needs of your project environment:

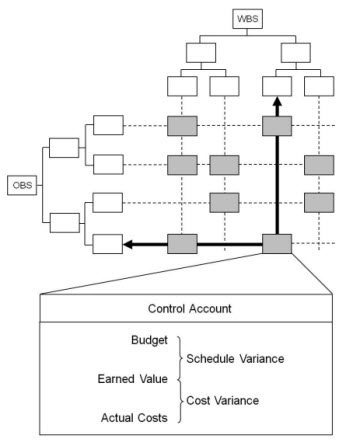

Answer the big three questions—As a rule, key stakeholders want to know the answers to the

following three questions when reviewing project performance:

1. Where do we stand (in regard to the critical success factors)?

2. What variances exist, what caused them, and what are we doing

about them?

3. Has the forecast changed?

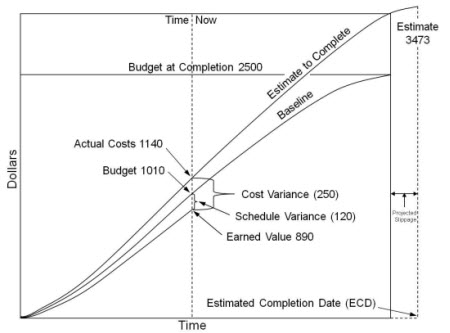

Measure from current baseline—If

you are going to report project performance with a variance focus, you must

establish and maintain your performance baselines. Any change to the

performance baselines is controlled via your change control procedures.

Think “visual”—Another

key concept in reporting is to think visually. Most people are visual and

spatial learners and will grasp the important project performance metrics more

quickly if they are presented in a visual format. The use of bar charts,

graphical schedule summaries, and stoplight indicators (red, yellow, and green)

for key metrics are good examples of this technique.

Think “summary page”—Along

this same theme, you generally want to provide your key status information in

no more than one to two pages. If it is appropriate to have details that will

take more than one or two pages, it is recommended that you provide a one

summary page upfront.

Highlight accomplishments—A

part of the status report’s function is to serve as a public relations tool for

the project, so make sure key accomplishments are highlighted prominently.

Show forecasts—In

addition to reporting how the project has performed to date, remember to show

the forecasted schedule and cost metrics. Often, this information is shown as

Estimated At Completion (EAC) and Estimated To Complete (ETC) figures.

Specifically, highlight any changes to these figures from the last reporting

period.

Highlight key issues, risks, and change requests—A natural category when assessing project performance. Make

sure any key issues, risks, and change requests are included on status reports.

Avoid surprises—An

important point about consistent, performance based

status

reporting is that stakeholders are aware and knowledgeable regarding overall

project status and are not caught off guard with project developments. To this

extent, depending on the audience for any status report, you might want to

communicate with specific stakeholders in advance of any official report

distribution. Always remember, don’t surprise anyone—especially your sponsors

and accountable senior management stakeholders.

Adapt to meet stakeholder needs—This is an example of the customer service orientation and

servant leadership qualities of effective project managers. Be prepared to

offer examples of performance reports that have worked well for you in the

past, but most importantly, go into any project looking to understand the

information needs for this given environment. Show enthusiasm and willingness

to adapt to the customer’s standards or to develop custom formats to best meet

the stakeholders’ needs.

Appropriate frequency—Consistent

with a management fundamental mentioned earlier, the frequency of performance

reporting needs to be appropriate for the project. The process of gathering

information and reporting performance needs to be quick enough and occur often

enough to be useful and relevant.

Variance Responses

As

we have mentioned, the first goal of our project control system is to prevent any

variance. However, we also realize variances and changes will occur—this is the

nature of the project beast. Thus, the remaining goals of project control are centred

on early detection and appropriate response. Let’s review the general response

options that are available to us (the project) when a variance occurs.

Take corrective actions—The

preferred option, whenever possible, is to understand the root cause of the

variance and then implement action steps to get the variance corrected. When

performance measurement is frequent, it is more likely that action can be taken

that will make a difference. Examples of corrective actions include adding

resources, changing the process, coaching individual performance, compressing

the schedule (fast tracking or crashing), or reducing scope (this would be

documented as a change request, too).

Ignore it—In

cases where the variance is small (and falls within an acceptable threshold

range), you might choose to take no action to resolve the deviation. Even in

these cases, it would be advisable to log the variance as a risk factor.

Cancel project—There

might be times when the appropriate response is to cancel the project

altogether. This response is more likely on projects where one or more key

assumptions have not held or when one or more of the critical success factors

has a very low tolerance for any deviations.

Reset baselines—While

taking corrective action is the preferred option for performance variances,

there are times when the variance cannot be eliminated. This is common on

knowledge-based projects and common on projects where the estimating

assumptions have not held. In these cases, a decision to reset the performance

baselines is made and approved. Then from this point on, performance is

measured from this revised baseline.